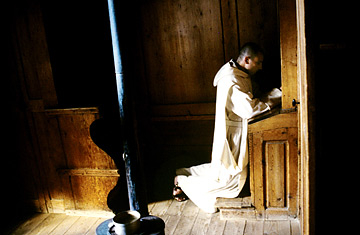

A monk of the Carthusian Order prays at their head monestary, the Grande Chartreuse, near Grenoble, France.

Director: Philip Gröning

Zeitgeist Films

Available Oct. 23; List Price $29.99

Most films work hard to win us over. They strain to entertain. This one, a study of the Carthusian monks of the Grande Chartreuse Abbey in the French Alps, is different. At the prom dance of contemporary movies, Into Great Silence stands apart, a mute among coquettes, its take-it-or-leave-it austerity exerting its own hypnotic pull. For 2hr.40mins. it follows the rigorous routine of these hermits as they meditate in their cells, pray together in chapel or take their weekly communal walk. The movie displays the unworldly joy these men take in their devotion to God and nature. In one lovely interlude, a half-dozen monks go shoe-skiing down a snowy hill, laughing and cheering one another along.

A sure bet for Best Documentary in the year-end critics' awards, Into Great Silence is a test of cinematic sanctity — for some viewers, a test of sanity. It is lusciously minimalist, asserting that less is enough. It renounces both dramatic conflict (there's no rebel in this monastery) and biographical back-story (what impulse, what need, what tragedy or epiphany took these men out of their secular lives and dropped them here?). The viewer must decide to join the monks in their self-discipline and devotion. "You are at God's disposal alone," one says, "in solitude and stillness, in an everlasting prayer and a joyful penitence."

Gröning first approached the monks about this film in 1984; he was told the time was not right. Sixteen years later he got the word, on condition he would come alone and shoot using only natural light. He spent six months in the abbey, observing the monks' regimen, trying to make a movie — a series of pictures of things — that would reveal their interior life.

I'm not sure the film resolves this dilemma. There's something contradictory in trying to understand the hermitic spirit by photographing it. We see a closeup profile of a monk praying over his texts — a man pursuing the vocation of solitude but with a cameraman in the room. It's as if Gröning is whispering, "No, go on, commune with God, pay me no attention. I will watch you read but not see what you read." The director does eventually confront his subjects directly. In mug shots of the monks, they blink a lot, as if being watched is something they're not used to. But they opened themselves to him, explained their calling. Surely they recognized a fellow seeker of serene truth — they in God, Gröning in art.

Other seekers will find the film its own object of contemplation, meditation, transcendence. This mostly non-talking film has the viewer talking back to it, considering first principles of moviemaking and movie-watching. In the cathedral of cinema, this is a unique, votive text.